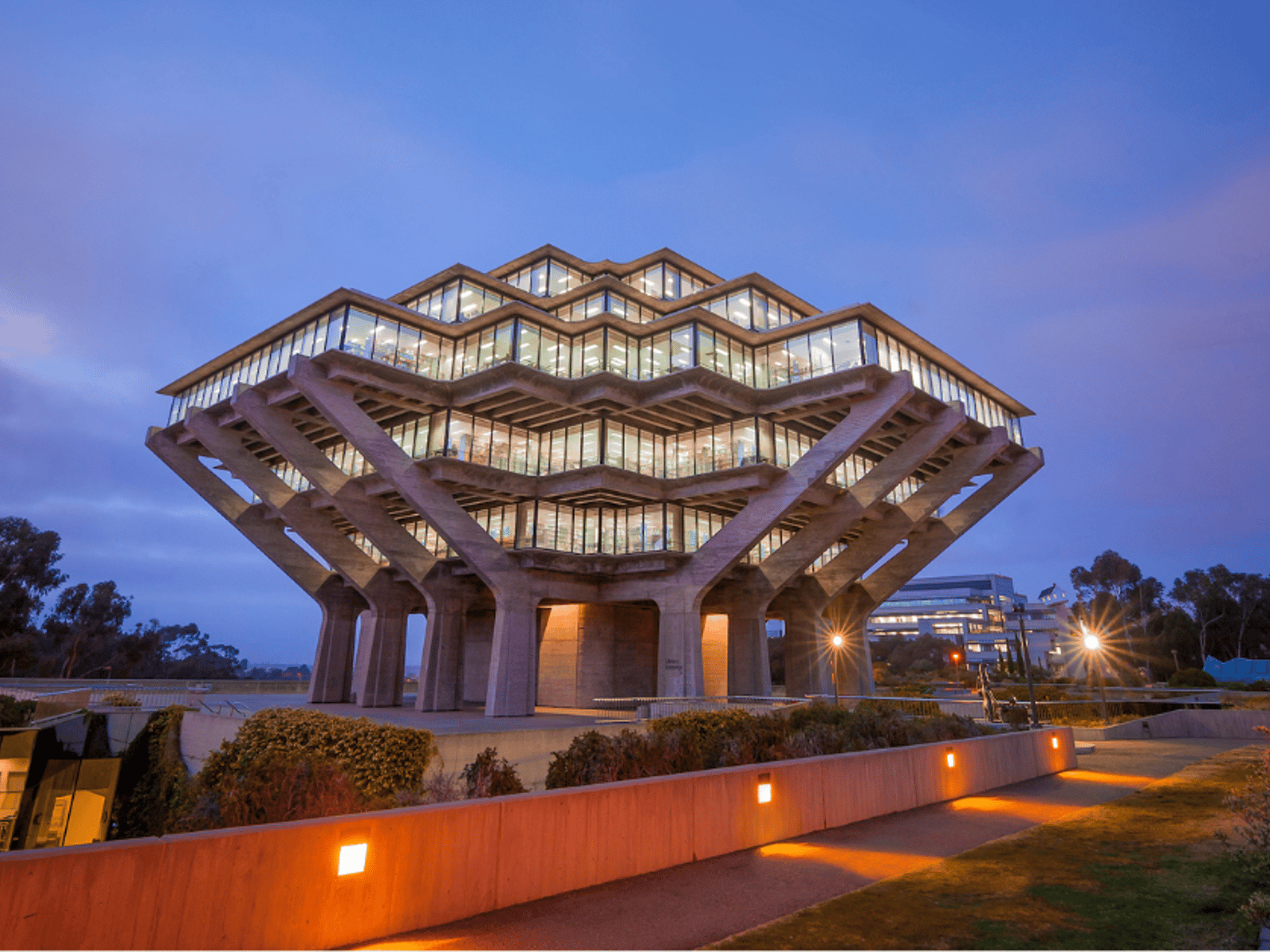

The UC San Diego Materials Research Science and Engineering Center fosters research, education, and outreach across the disciplines of engineering, physical sciences, and biological sciences, with a focus on new materials and new materials properties. It is developing two major themes: using computational models to predict and guide the self-assembly of materials from the nano- to mesoscales; and deploying the tools of synthetic biology to create soft materials that incorporate living components.

Predictive Assembly

Rational materials design and development guided by a computational framework, validated by experimental measurements

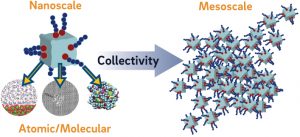

Long-term Research Goals and Intellectual Focus: The intellectual focus of IRG1 is on the assembly of nanoscale building blocks into functional, tunable materials that operate at the meso- to macroscales. The ability to organize nanoscale components rationally, precisely, and collectively into larger-scale architectures will enable limitless possibilities for creating materials that are poised for broad impact in energy security, environmental sustainability, human health, and civil infrastructure. However, there is community consensus that coupled experimental and computational tools are a critical missing link for understanding materials function and scientific discovery at the mesoscale.

Our long-term research goal is to establish a computation-driven framework for understanding, predicting, and designing how nanocomponents dynamically assemble into complex mesoscale architectures. While the proposed framework is broadly applicable to a variety of systems, we will focus our investigation on two major materials systems where predictive mesoscale assembly has strong potential to lead to revolutionary scientific and technological advances.

Polymer-grafted nanocrystals (NCs): Solid-state NCs—here, composed of metal and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)can be synthesized into various anisotropic shapes by controlling crystallographic nucleation and growth. When grafted with polymers, NCs assemble into a rich variety of non-close-packed architectures that are phases unto themselves and exhibit unique optical and catalytic properties.

Natural and synthetic proteins: Supramolecular protein arrays can be assembled through both chemically and genetically controlled molecular-level interactions. Reversible metal coordination, disulfide bonding, and synthetic linkers minimize the burden of designing and engineering extensive protein surfaces, while enabling the construction of porous and gel-like materials that are modular, responsive to external stimuli, and retain biological function.

Engineered Living Materials

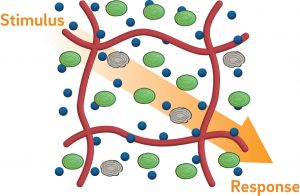

The intellectual focus of IRG 2: Engineered Living Materials is to develop methods to integrate engineered living matter with polymeric materials. In doing so, we will create new composite materials that are responsive to diverse stimuli and capable of generating complex, genetically encoded material outputs. Our long-term research goals are to develop techniques that will enable the creation of materials at the living/non-living interface, with the potential for use in biosynthetic electronics, chemical threat decontamination, therapeutic synthesis/delivery, and soft robotics, among other applications. To accomplish these goals, we will integrate genetically-modified photosynthetic organisms (e.g., cyanobacteria, plant cells, and algae) with polymeric materials through gel immobilization, patterning on flexible/elastomeric substrates, or deposition onto mechanically robust films. Within these materials, genes will be activated in response to a specific stimulus that will control material properties. Our proposed research goes beyond bio-mimetic or bio-inspired materials; living systems and polymeric materials will be synergized to achieve unprecedented control of material properties and function in the emerging area of engineered living materials. Fundamental challenges inherent to living materials will be pursued in the context of three research thrusts:

Stimuli-Responsive Biosynthetic Materials. Fabricate biosynthetic composite materials by integrating engineered cells into gels, 3D-printed structures, and elastomers to develop materials that are chemical factories. Current stimuli-responsive materials lack a diversity of inputs and consequently respond with modest material outputs. We will create materials that respond genetically to specific, diverse stimuli—e.g., chemical threat exposure, circadian cycle, and disease states—and produce a range of outputs, including threat deactivation, cyclical thermal insulation, and triggered therapeutic production, respectively.

Photosynthetic Electronic Materials. Pattern and synthesize polymer electronic materials using photosynthetic organisms. Engineered cells offer the ability to perform complex biosynthetic chemistry to form monomers for conducting polymers (e.g., thiophene or pyrrole), as well as oxidative polymerization catalysts (e.g., peroxidases). We will engineer plant cells, cyanobacteria, and algae to synthesize these components in response to light (optogenetics). These cells will be integrated into polymeric substrates by roll-to-roll manufacturing, gel encapsulation, and soft-lithography to yield biocomposite materials that can be photolithographically patterned into electronic circuits.

Auto-Regenerative and Shape-Shifting Materials. A single-step genetically controlled polymerization will be initiated by engineered cells to achieve auto-regeneration of damaged materials and material folding (i.e., polymer origami). Genetically engineered cells that produce olefin monomers and metal-free catalysts for controlled radical polymerization (CRP) will be incorporated into polymeric materials. Once activated, the engineered cells will produce all requisite material for CRP that will produce polymers with diverse mechanical properties. We anticipate using these composites to heal material damage (i.e., auto-regeneration) and to induce complex geometric changes by generating asymmetric forces through differences in mechanical properties.