Highlights

May 25, 2016

UPENN Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers

6th Annual Philadelphia Materials Day

A. R. McGhie & M. W. Licurse

The 6th annual Philadelphia Materials Day was held on Saturday, February 6, 2016 at the Bossone Research Center at Drexel University. This joint venture between Penn and Drexel Universities was attended by over 1100 students and parents. Each year faculty and their students present demos on materials-related themes of interest to K-12 students. The themes this year were: Communications, Earth, Environment, Energy, and Sports.

May 25, 2016

UPENN Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers

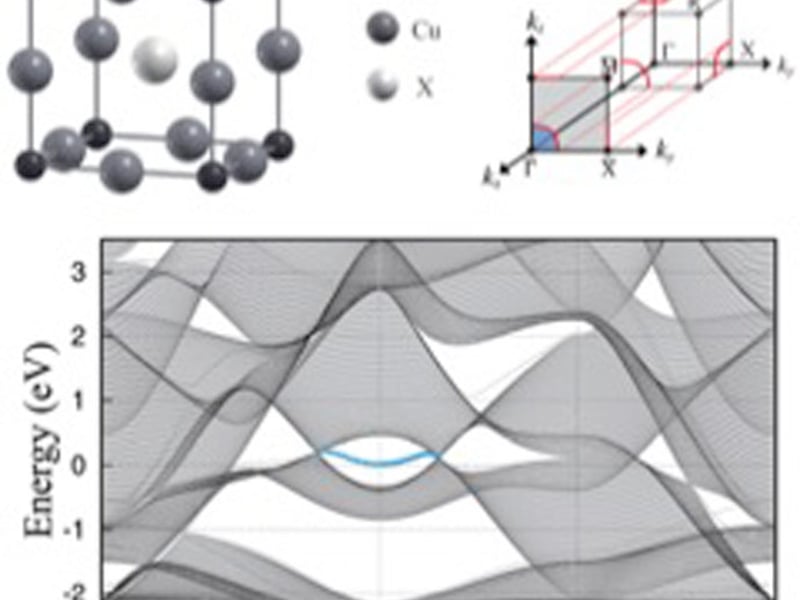

Dirac Line Nodes in Inversion Symmetric Crystals

C. L. Kane & A. M. Rappe (SuperSeed 1)

Topological insulators, which were first introduced at Penn, are new materials with novel features such as protected states that hold potential for quantum computing. We have identified a class of 3D crystals that feature a new kind of topological band phenomena: Dirac line nodes (DLN). These are lines in momentum space where the conduction band and valence band touch, and their degeneracy is required by inversion symmetry even in the absence of spin orbit interactions.

May 25, 2016

UPENN Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers

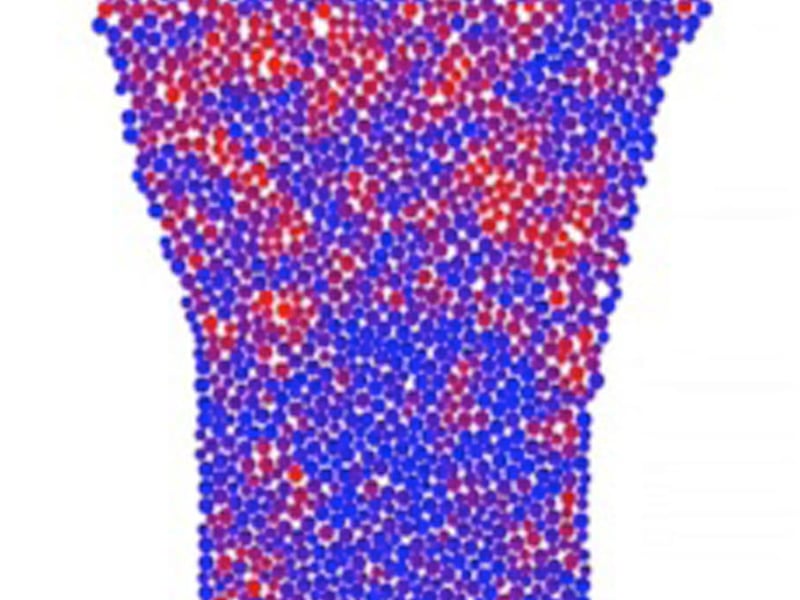

Identifying Structural Flow Defects in Disordered SolidsUsing Machine Learning Methods

D. J. Durian, E. Kaxiras (Harvard MRSEC), A. J. Liu (IRG-3)

We are often taught that the difference between solids and liquids is that in solids, each of the constituent particles has a well-defined average position while in liquids, particles are constantly rearranging and changing their neighbors. In fact, particle rearrangements do occur in solids, and all solids flow under enough stress. Crystalline solids flow via localized particle rearrangements that occur preferentially at structural defects known as dislocations. The population of dislocations therefore controls how crystalline solids flow.

May 25, 2016

UPENN Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers

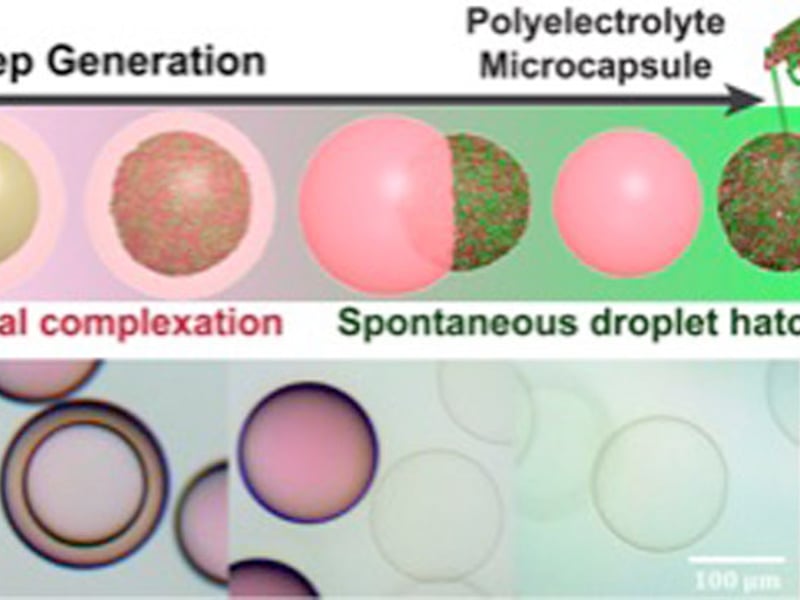

Nanoscale Interfacial Complexation in Emulsion (NICE)

D. Lee & J. A. Burdick (IRG-2)

Microcapsules that encapsulate and protect molecules and materials by forming isolated aqueous compartments inside hollow shells are widely used in a variety of applications in the food, pharmaceutical, cosmetics, and agriculture industries. One promising method that has emerged is layer by layer (LbL) assembly, but this method to make microcapsules has low encapsulation yield, is tedious, and is time consuming.

May 25, 2016

UPENN Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers

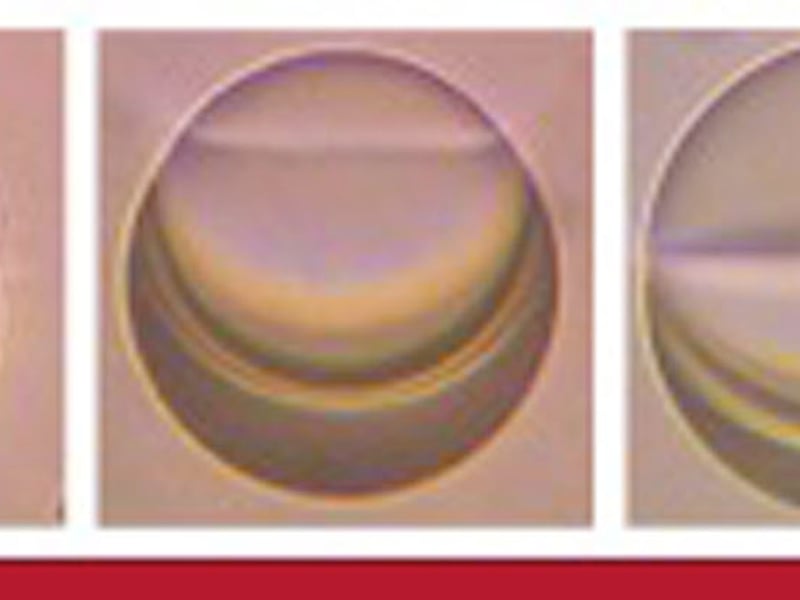

Liquid Crystal Janus Droplets

D. Lee, P. Collings, & A. G. Yodh (IRG-1)

Janus colloids are composed of two-faced particles with distinctive surfaces and/or compartments. Lee, Collings, & Yodh have created the first Janus particles with a liquid crystal (LC) compartment. The droplets were prepared by combining microfluidic and phase separation techniques, and the LC compartment morphologies can be easily controlled to realize unique confining geometries (Fig. 1).

May 25, 2016

UPENN Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers

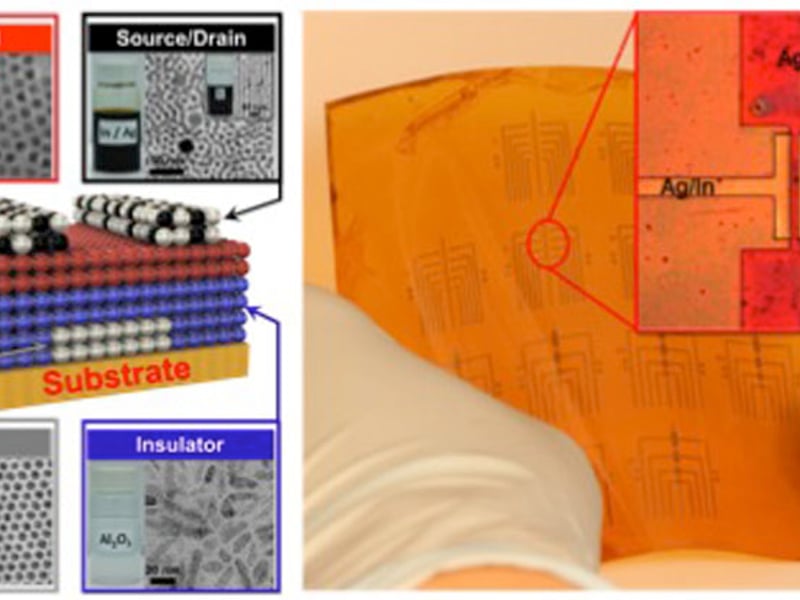

All Nanocrystal Electronics

C.B. Murray & C.R. Kagan (IRG-4)

Synthetic methods produce colloidal nanocrystals that are metallic, semiconducting, and insulating. These nanocrystals have been typically used to form only a single component in devices. IRG-4 has exploited the library of colloidal nanocrystals and designed the materials, surfaces, and interfaces to construct all the components of field-effect transistors.The transistors are fabricated from solution over large areas and on flexible plastics and have excellent electrical performance.

This work was published in Science, 352, 205-208 (2016).

May 25, 2016

CRISP: Center for Research on Interface Structures and Phenomena (2011)

Revealing Hidden Phases in Materials

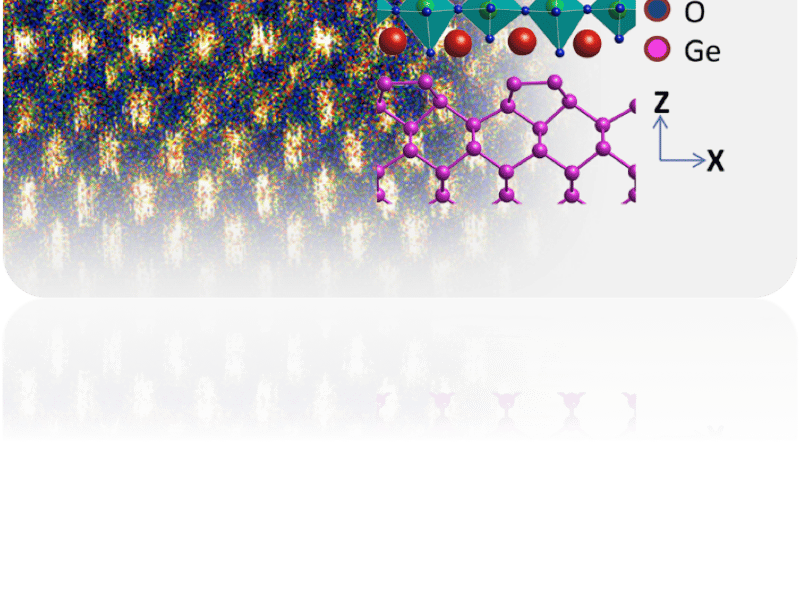

Ismail-Beigi, Ahn, and Walker

Strong interactions at the interface between a crystalline film and substrate can impart new structure to thin films.

Here, a germanium surface (purple atoms) squeezes a BaTiO3 thin film above, revealing a hidden phase not seen in the bulk. The hidden phase of BaTiO3 shows oxygen octahedra cages (shaded in aqua) alternating in size.

By combining theory, synchrotron x-ray diffraction, and electron microscopy, a new materials design approach has uncovered hidden traits of a material that can be expressed through articulated forces at an interface.

May 25, 2016

CRISP: Center for Research on Interface Structures and Phenomena (2011)

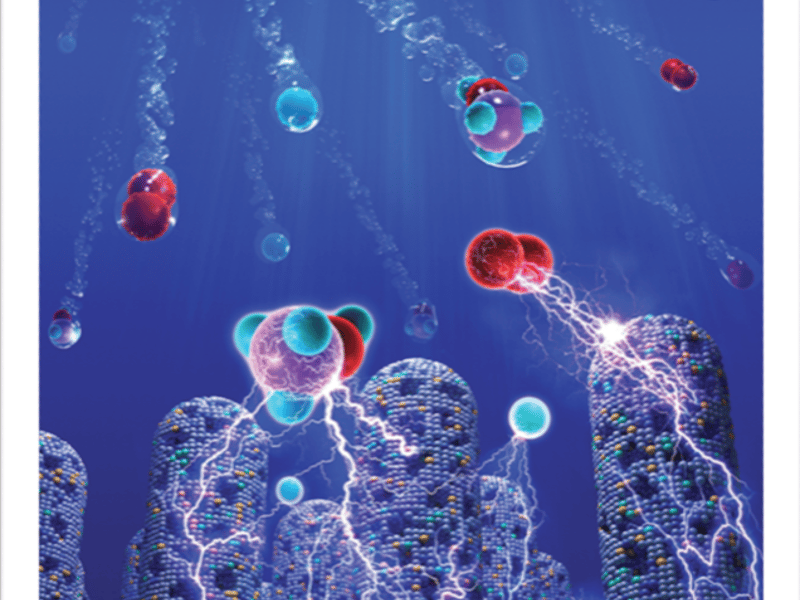

Electrocatalytic Surfaces Using Bulk Metallic Glass Nanostructures

Osuji, Schroers, and Taylor

Metallic glass nanostructures provide a new platform for electrocatalytic applications. Several surface modification strategies that remove or add metal species (top images) improve the catalytic activity of metallic glass nanostructures. These strategies were demonstrated for three key electrocatalytic reactions important for renewable energy.

May 18, 2016

Next Generation Materials for Plasmonics and Organic Spintronics (2011)

Leveraging MRSEC Equipment Purchases

Ian R. Harvey, Shared Facilities Director, Utah MRSEC, University of Utah

Leveraged

upgrades to Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope (S/TEM) and Focused Ion

Beam System (FIB):

May 18, 2016

Next Generation Materials for Plasmonics and Organic Spintronics (2011)

Modeling the UV Electromagnetic Response of Al and Mg Plasmonic Nanostructures

Steve Blair, Department of Computer and Electric Engineering, University of Utah Sivaraman Guruswamy, Department of Metallurgical Engineering, University of Utah

Objective:

Compare the UV plasmonic response of Al and Mg nanostructures. Light

transmission through sub-wavelength aperture arrays shows significant

Showing 541 to 550 of 1394